Are ACL Injuries Preventable?

- Kris Krotiris

- Mar 27, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 28, 2024

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is an important stabilising ligament in the knee, and injuries to it are a common concern among athletes and fitness enthusiasts. The anxiety surrounding ACL injuries stems not only from their prevalence but also from the extensive and challenging recovery process they often require. This naturally leads to important questions: Are these injuries preventable, and if so, what steps can be taken to reduce the risk?

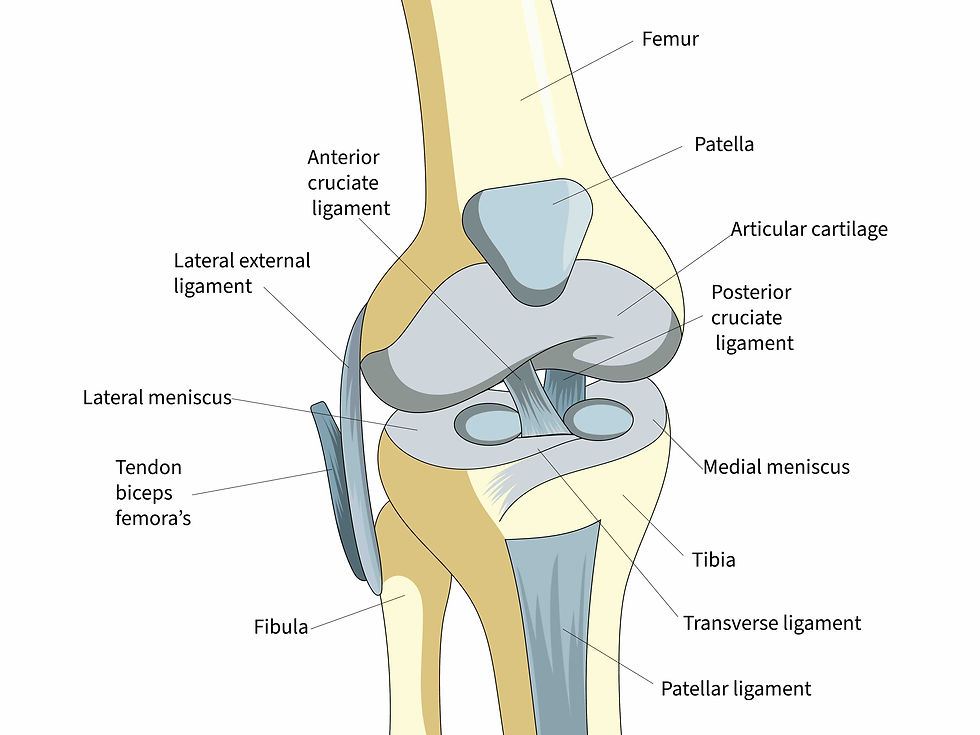

Anatomy and Function of the ACL

The ACL is one of the key ligaments that help stabilise the knee joint. It connects the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia) as shown in Figure 1 below and plays a pivotal role in controlling the back-and-forth and rotational motion of the knee. The ACL is crucial for providing the knee with the stability needed for activities like running, jumping, and quickly changing direction. Its importance is particularly evident in high-demand sports where intense agility movements frequently challenge this stability. Understanding the function of the ACL is the first step in recognising why injuries to this ligament can be so impactful and why their prevention is of significant interest.

How Does An ACL Injury Occur?

It may not seem like much, but analysing the pictures below reveals two typical scenarios leading to an ACL injury: the knee buckling inwards when landing from a jump or during a change-of-direction movement. This buckling movement, particularly when the knee is flexed to 20-30 degrees, puts a large amount of force through the ACL, which can lead to a tear, as was the outcome in the two athletes seen below. Hyper-extension of the knee is another common mechanism by which an ACL injury can occur. Unfortunately, the ACL very rarely heals itself. For high-level athletes, this often means surgery to reconstruct this important ligament and 10-12 months of rehabilitation.

Why do ACL injuries happen?

Some studies have identified clear factors that may increase the risk of an ACL injury. These include:

The size and shape of the intercondylar femoral notch: This refers to the specific notch at the end of the thigh bone.

The depth of the medial tibial plateau’s concavity: This refers to how deep the inward curve is on the top of the shinbone, specifically on the inner side.

The slope of the tibial plateaus: This describes the angle or incline of the top surfaces of the shinbone.

Knee joint hypermobility: The ability of the knee joint to move beyond its normal range of motion, often referred to as having “loose” or “extra flexible” knees.

Separate risk factors for repeat injury following an ACL reconstruction should also be considered, given the high rate of re-rupture following surgery. These include:

Improper graft placement: During surgery, if the graft is not aligned correctly with the natural orientation of the original ACL, it can lead to complications such as limited knee function, instability, or even re-tearing of the graft. Proper alignment is crucial for the graft to function like the original ligament, allowing for normal knee movement and stability.

Inadequate or incomplete rehabilitation before returning to sport: This most commonly involves:

Impaired quadriceps strength: This remains a significant risk factor for repeat ACL injuries. The quadriceps are key muscles in supporting and stabilising the knee joint. After an ACL injury or reconstruction surgery, these muscles often weaken due to disuse or protective inhibition—a natural response of the body to pain and injury.

Impaired neuromuscular control: Neuromuscular control of the knee refers to its ability to perceive its position in space, which is essential for preventing awkward movements that can lead to re-injury. Following an ACL injury, neuromuscular control is impaired and needs to be worked on through specific rehabilitation exercises.

Lack of sport-specific training: It’s crucial for athletes to undergo adequate, tailored training that aligns with the specific demands of their sport before engaging in competition. This type of training ensures that athletes are not only physically prepared—with the necessary skills, strength, and agility—but also mentally confident to safely compete.

The level of an athlete’s preparedness for their specific sport might influence their risk of a first-time ACL injury, though the exact relationship is not definitively clear. Theoretically, certain factors that increase strain on the ACL during sports activities should be considered. These include:

Poor jumping and landing techniques: For instance, knees collapsing inward (valgus collapse) when landing from a jump. This improper technique can increase the stress on the ACL.

Increased Body Mass Index (BMI): A higher BMI may contribute to greater stress on the knee joints during physical activities, potentially increasing the risk of ACL injuries.

Lack of sport-specific training: Insufficient training and exposure to the specific demands of a sport before competition can leave the athlete unprepared for certain movements, leading to a higher risk of injury.

Increased Q-angle: This is particularly relevant for women. The Q-angle is the angle formed by the quadriceps muscles and the patella tendon. A larger Q-angle is thought to put more strain on the knee, possibly increasing the risk of ACL injuries in women.

Research has indicated that these factors, among others, may contribute to the likelihood of sustaining an ACL injury. Therefore, tailored training and conditioning programs that target potentially modifiable risk factors (e.g. training preparedness, BMI and landing technique) should be considered, particularly in sports with high demands on knee stability and strength.

Can ACL injuries be prevented?

Research indicates that implementing an injury prevention program, particularly one that emphasises neuromuscular control of the knee and hip, may modestly reduce the risk of first-time ACL injuries. These programs typically focus on improving the coordination and strength of muscles around the knee and hip joints to enhance stability and correct movement patterns. However, the exact details and most effective components of such programs are not yet fully established. While the broad principles are understood—like strengthening, balance training, and agility exercises—the specifics regarding the most effective exercises, their intensity, duration, and frequency are still subjects of ongoing research.

Ultimately, each athlete’s risk is determined by the interplay between the mentioned risk factors and more. The best you or any athlete can do to prevent such an injury is to focus on correcting any modifiable risk factors with the guidance of your physiotherapist. Tailoring a program to individual needs and sport-specific demands could potentially enhance the effectiveness in reducing ACL injury risk.

If you have had a previous ACL injury or would like to implement an injury prevention program to reduce your future risk of injury, get in touch with us for an appointment. You can book online or call us on 0415 889 903. If you’d like more information, send us an email at kris@prosportphysio.com.au.

Comments